Urbanizing Dead Suburban Malls: What Works?

In recent months there’s been a lot of talk about dead suburban malls and what we should do with them. Last September Ellen Dunham-Jones of Retrofitting Suburbia fame (co-authored with June Williamson) got the ball rolling in an interview with Steve Inskeep on National Public Radio. PBS Newshour sustained the momentum in December. Earlier this month writers at the New York Times and Washington Post weighed in.

This topic is of interest because Denver has been retrofitting its dead and dying suburban malls for a while now, on a New Urbanist “town center” model. More than half of our dozen or so regional malls are already retrofitted, and more are being repurposed as we speak.

Dunham-Jones routinely identifies Belmar on the site of the old Villa Italia Mall in suburban Lakewood as a retrofit success story, distinguished by green buildings, great connectivity, and a nice “sense of place.” Simmons Buntin concurs in his chapter about Belmar in Unsprawl: Remixing Spaces as Places.

He pitches Belmar as “a model for redeveloping suburban malls across the U.S.” Alan Ehrenhalt, in The Great Inversion, casts Denver as “the emerging capital” of America’s suburban town center phenomenon.

Because Denver is such a busy incubator of New Urbanist theory and practice it offers numerous opportunities for students to do original fieldwork in urban anthropology. For the last three years I’ve been sending students in my “Culture and The City” course around town to compare and contrast three suburban mall retrofits. These include Belmar, CityCenter Englewood, and The Streets at SouthGlenn.

Their task is to (1) discuss how each project conforms to New Urbanist goals and ideals; (2) critically evaluate their prospects for success in light of current ideas about urban ecological and cultural sustainability; and (3) identify the one development that they would choose to live in and explain why.

I ask them to look, listen, and interview the users of each place as the opportunity allows; in other words, I ask them to do a little urban ethnography. I urge them to make multiple visits to their field sites, on different days and at different times of day.

The course enrolls majors from across the Arts and Sciences and students minoring in sustainability. I get a few anthropology graduate students working in the areas of archaeology and museum and heritage studies. It’s not an especially diverse group in terms of ethnicity, given that the University of Denver is a largely white institution. But I do get some minority students, mostly Latinos. Exchange students from the United Kingdom, Italy, Eastern Europe, and Africa contribute a unique international perspective.

Thus, the Retrofitted Mall assignment is an excellent opportunity to learn what kind of urban development best resonates with a demographic that’s migrating to American cities in droves.

Students prepare for the assignment by reading some combination of the following:

- Charter of the New Urbanism;

- an excerpt from chapter seven of Phil Wood and Charles Landry’s The Intercultural City: Planning for Diversity Advantage;

- Jeb Brugmann’s chapter on “Building Local Culture: Reclaiming the Streets of Gràcia District, Barcelona” in his Welcome to the Urban Revolution;

- essays by Mohammed Qadeer on multicultural planning;

- James Rojas on Latino Urbanism;

- Allison Arieff on the American Dream;

- Buntin’s chapter in Unsprawl;

- and Mike Davis’s chapter on “Fortress LA” in City of Quartz;

- they’re also urged to dip into a previously assigned classic from Jane Jacobs.

I guide students to some concepts in this body of work that strike me as especially relevant. Foremost among these is Wood and Landry’s notion of “cultural literacy” and how the “basic building blocks of the city”—street frontages, building heights, set-backs, public space, etc.—look different when viewed through “intercultural eyes.”

I want students to consider the extent to which New Urbanist projects exemplify the Barcelona urbanist’s particular concept of espai public—defined as a distinctive “third territory of streets and squares where private interests and public uses are vitally interwoven.”

Davis’s book is a veritable cornucopia of useful and provocative concepts. I ask students to ponder his notions of “spatial apartheid” and the “archisemiotics” of built form—the latter broadly understood to cover the meanings conveyed by a project’s architecture, advertising images associated with its effort to create a distinctive identity, and other features of the designed environment.

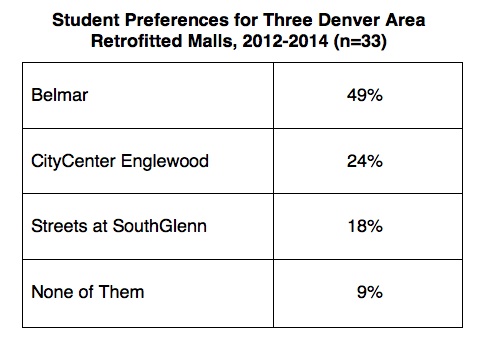

The table above presents the results from three years of student reports. Forty nine percent of the students would choose to live in Belmar. However, a slim majority of 51 percent prefer something else or nothing at all.

I provide a detailed summary of the more typical student comments about each retrofit over at Planetizen.

Here’s the punchline: Denver’s suburban mall retrofits have a decidedly mixed appeal for college-age Millennials.

Their experience in, and evaluation of, these places can be very different from those of professional planners and opinion-shapers. In class discussion it’s often hard for students to remember which retrofit is which. They blur together in the mind and are often confused, the starkest differences between them notwithstanding.

Formulaic plans widely applied aren’t conducive to creating a unique “sense of place.” Thus, Ellen Dunham-Jones’ assessment in a recent public lecture at the University of Colorado’s College of Architecture and Planning that Denver has “figured it out” might be a bit premature.

Still, students are inclined to be charitable. They see each of these developments as a work in progress. Their biggest challenge is attracting ethnic diversity and a mix of incomes. At some (e.g., Belmar) students seem to be noticing more Latinos patronizing the shops and open spaces. At others, however, ethnic diversity is primarily observed among the custodial and landscaping staff (e.g., The Streets at SouthGlenn, photographed above).

It’s safe to say that Denver’s New Urban mall retrofits still signal—to Americans, Europeans, and ethnic “Others” alike—homogeneity and exclusivity.

This gives one pause to wonder whether New Urbanism as applied to dead suburban malls can really succeed in accomplishing, at the same time and within the same program, its diversity, equity, and community-building goals.

Wood and Landry challenge planners and architects interested in intercultural city-building to either structure space so that different cultures might see and use it in a variety of ways, or create more open-ended spaces to which a broad variety of intercultural Others can adapt (perhaps along the lines of an entropic urbanism).

Some students wish to challenge New Urbanism in the same way. Alternatively, one student questions whether New Urbanism is capable of producing an intercultural city at all. As she puts it, perhaps an intercultural city already exists in the urban fabric and just needs some poking and prodding—using other varieties of urbanism as a guide—to draw it out.