Unintended Consequences: When Environmental "Goods" Turn Bad

By François Mancebo, Paris

I recently listened to this short podcast from TNOC: "Closing the Sustainability and Equity Gap: What does it mean to be both a green and just city?" It was the conclusive debate of the 2014 MAS (Municipal Art Society) Summit for New York City, with Toni Griffin and (SCC Advisory Committee member) David Maddox as the two debaters.

I was sitting comfortably in my favorite armchair, sipping coffee and listening to this podcast with my headphones on, when all of a sudden I heard: "We have been relatively good at discussing—not enough, but relatively good—at discussing the idea of environmental bads…" The whole idea was that we had not paid sufficient attention to environmental goods.

"Green spaces"—especially linear parks—were described as paragons of environmental goods.

I started thinking, Wow. Really? This idea stuck in my mind, because it clashed with my own experience.

I am not convinced at all that actual urban policies focus mainly on what we could call environmental bads: building eco-districts and designing environmental friendly areas is creating environmental goods; both smart cities and resilient cities—two different and somewhat contradictory approaches—focus on the bright side of sustainability (designing the future) rather than the bad side.

Besides, I am also unconvinced that green spaces are inherently "positive", both from an environmental and social point of view.

They may even, on some occasions, generate very negative and unexpected side effects.

The failure of Seine-St-Denis

In one of my more recently published articles — Combining Sustainability and Social Justice in the Paris Metropolitan Region — I showed that creating environmental goods and amenities such as parks "out of the blue" is absolutely not sufficient to enhance urban justice, be it distributive, restorative or interpersonal.

Look at Seine-St-Denisnear Paris, a case that deserves special attention.

At the scale of the Paris metropolitan region, this area has a very poor image due to its industrial heritage and the presence of large social-housing units.

It is associated with environmental shortcomings and low quality of life.

Parisians usually avoid this area because they see it as ugly and unsafe, while most of the inhabitants of Seine-St-Denis have the feeling that they live in a bad place, in which they consider themselves abandoned.

They'd like to relocate, but they generally lack the financial ability to do so, or they are stuck in this area by their professional activity.

So, their sense of belonging to the place they live in, their sense of ownership, and finally their self-esteem, are very low.

A book about the industrial heritage of Seine-St-Denis between 1850 and 2000—Dangereux, insalubres et incommodes: paysages industriels en banlieue parisienne (XIXe-XXe siècles)—shows that the prejudice against Seine-St-Denis is strong.

But guess what? The deindustrialization of Seine-St-Denis happened forty years ago.

Since then, countless major urban regeneration and urban reconfiguration programs were developed, as explained by Sylvie Salles in her article "La reconversion de la Plaine Saint-Denis, le paysage à l'épreuve du territories".

Parks were created in former wastelands and brownfields; linear parks were designed along formal industrial transit roads, railroad tracks, and canals.

Eco-districts of social housing were built, connected by hundred kilometers of tram tracks, new subway lines, and soft mobility systems (bikes and pedestrian paths).

Better still, cultural amenities such as museums, libraries and theater companies were financed.

Attractive heritage sites, such as Basilique de St-Denis—a very important one—or the industrial sites of the 19th century were restored with increased access for everybody.

There are also two universities in Seine-St-Denis now.

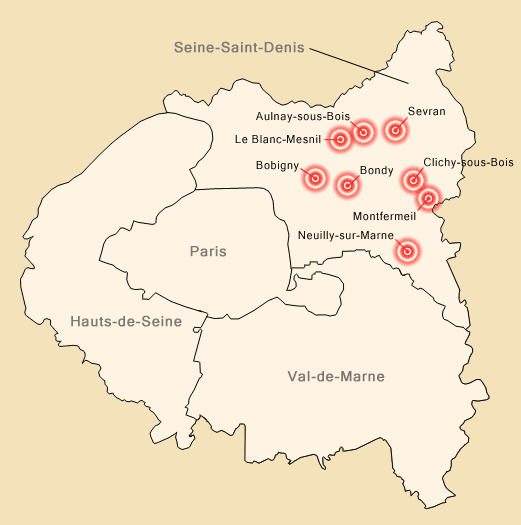

Map of Paris urban riots of 2005. Only the Seine-St-Denis is concerned in the whole Paris metropolitan region. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Very little has been done to cope with the environmental bads, such as polluted soils or traffic noise.

A lot of money has been invested to enhance or create environmental goods in Seine-St-Denis, yet nobody wants to live there.

It remains a "bad area" and a stigmatizing place, whatever efforts have been made there.

It is surely not a coincidence that almost all of the last years' French urban riots took place in Seine-St-Denis.

The good, the bad, or the ugly: which should we prioritize?

Let's play the devil's advocate and consider what happens when urban policies focusing on environmental goods, green amenities, and nice ecosystem services, succeed in creating attractive areas.

Is this situation positive for urban equity and urban justice? A first observation: urban injustice in the Paris metropolitan region increased significantly during the last twenty years.

Curiously enough, this co-ocurred with the rising of sustainability policies.

Was this some sort of accident? Probably not! In his article "Selective public policies: sustainability and neoliberal urban restructuring", Vincent Béal points out that urban policies changed in the 1990s, as the sustainability issue became a top priority in a context of urban neoliberalization.

Policies shifted with the development of a very aggressive urban marketing initiative designed to attract upper classes and the so-called "creative" classes to urban centers.

This new orientation—linking together environmental and economic objectives—naturally induced spatial segregation and urban injustice, since poor people lost access to nice natural and living environments because they couldn't afford to live in such locations anymore.

Thus, green policies based on environmental goods may result in dramatic—if not intentional—negative side effects for urban justice.

All things considered, there may be some good sense in coping first with the environmental "bads", which, by the way, is not such a frequent attitude in real life.

In the Paris Metropolitan Region, nearly 70 percent of the socially-deprived communes (the smallest local administrative division in France, governed by a mayor and a council) are exposed to cumulative nuisances, mainly north of Paris—essentially, Seine-St-Denis and Val-d'Oise.

The west, the south,and Paris itself enjoy fewer nuisances and are inhabited by wealthy people.

What are the determinants of such a distribution? Is it the attractiveness of a nice environment, or the avoidance of such nuisances? Put another way: is it the environmental "goods", or the environmental "bads"? A report shows that in the Paris metropolitan region, nuisances and environmental degradation are the main reasons for people to move from the place they are living.

Thus, the decision to move is strongly correlated to the desire to avoid environmental bads.

This rejection is stronger than the attractiveness of environmental amenities (nature, silence, air and water quality, etc.).

The question is: why? Why is the avoidance of real or imagined bad environmental conditions more decisive in explaining spatial distribution? Why does—in the case of the Paris region— the creation of amenities, green areas, or accessible ecosystem services have virtually no effect on attractiveness?

Creating environmental goods (Plage Bleue in Valenton). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

There are probably many reasons, and I hope that comments on this post will uncover a spectrum of answers.

My answer is this: the environment cannot be reduced to those biophysical aspects that embody a proper functional integration of urban ecosystems.

In France, so called "green spaces", when coupled with social housing—as in Seine-St-Denis—are perceived by their inhabitants as buffer zones, created to separate them from the rest of the city.

Conversely, the people living outside perceive them as dangerous areas frequented by rapists and dealers, as areas embodying fantasies about the social housing blocks.

The result is that nobody ever uses these parks, even though they were originally designed to foster social and cultural intermingling, and to encourage social diversity.

How ironic is that?

Maybe not so ironic—maybe perfectly in line with Parisian urban history.

When Haussmann introduced greenery in the 19th century, one of his secondary objectives was to control the use of public space through a technical approach based on hygienism.

The initiative's main function was to bring more sunlight to the city and to better the air circulation.

But, by doing so, the city's life was marked by socio-spatial differentiation that was virtually segregative, embodied in a type of re-vegetation reduced to espaces verts.

The very term espace vert (green space) instead of park or garden reveals its real nature: an indistinct area whose boundaries are decided in the abstract world of master plans.

Nowadays, the same logic maintains itself: to separate, to distinguish, and to hide.

The current regional master plan of the Paris metropolitan region proposes a quantitative objective of 10 m2 of public green area per inhabitant, as though it were sufficient to display a "green" label to become suddenly friendly and sustainable.

The real issue is, does such a green label enable belonging and inclusion?

Indeed, one among the many challenges of urban sustainability should be developing the inclusiveness of the urban social fabric—a complex task—instead of adding parks and ecosystem services, which is relatively easy.

Usually mayors, representatives, and other elected officials are not interested in improving what is already here, and they don't like long-term commitments; their time horizon is usually the end of their term.

There is no way to foster belonging and ownership in such a context.

Defining a good environment for green and just cities

What happens without dealing with the existing environmental bads (rail yard, gare de triage, and parking in Valenton, just behind the Plage Bleue). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

To design both a green and just city, it is crucial to know what a "good environment" is for the people and the communities living there, one in which the enhancement of environmental conditions improves living conditions and facilitates new lifestyles.

A polluted environment can be a place where life is good.

Just think about the price of a square meter in the very center of very noisy and very polluted Manhattan, Paris, or London.

Conversely, an environment with clean air and clean water can be quite intolerable, as evidenced by windswept, segregated social-housing blocks settled in the middle of nowhere.

This logic was reflected at the beginning of the TNOC podcast, which noted that urban justice is not only about equity, fairness and distribution—to affordable housing, for example—but also about choice and inclusion, which goes with ownership and participation in decision-making.

Finally, it is about the right of the inhabitants to be creative and to build a beautiful environment.

I could not agree more.

It follows, then, that both "green" and "just" policies should include among their deciders not only elected officials and companies, but also non-market institutions, local communities, and individuals able to form self-determined user associations, according to the idea of Elinor Ostrom's work, who showed that user communities can manage common goods quite well.

An incinerator in the back of a park in St-Ouen. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Nobody is saying that it will be easy, but these principles are a necessary prerequisite for fostering collective appropriation of environmental policies by the inhabitants.

Governing and managing a city by definition is a "wicked problem": a problem that is difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize.

Moreover, because of complex interdependencies, the effort to solve one aspect of a wicked problem may reveal or create other problems (Rittel and Webber 1973).

Such problems are made all the more difficult because they combine environmental action and social justice.

As Bruno Latour and Michel Callon beautifully put it in their seminal article, "Unscrewing the Big Leviathan":

"There is no overall architect to guide it, and no design, however unreflected.

Each town hall and each promoter, each king and each visionary claim to possess the overall plan and to understand the meaning of the story… Here and there one retires within oneself accepting the fate decided by others.

Or else, one agrees to define oneself as an individual actor who will alter nothing more than the partitions in the apartment or the wallpaper in the bedroom.

At other times actors who had always defined themselves and had always been defined as microactors ally themselves together around a threatened district, march to the town hall and enroll dissident architects.

By their action they manage to have a radial road diverted or a tower that a macro-actor had built pulled down…"

Yes, fostering co-construction, inclusiveness, and ownership in urban policies is no picnic.

But curiously, it usually works better when nobody tries to frame the procedure.

It works better when nobody "looks"—when no public or private actor explains from the beginning to the population what the procedure should be, how people should act, and what should be their objectives.

In my next post, I will present the case of a squatted wasteland in a poor place near social housing blocks—an environmental "bad"— that turned into a very popular park, combining leisure amenities and urban agriculture.

In this case, an environmental bad was successfully converted into an environmental good precisely because no local authority or private company interfered.

The inhabitants created this place by themselves, seeking their own objectives.

In the end, the local authorities had no choice but to formalize what the community had already built.

Meanwhile, let me invite you to join the 5th Rencontres Internationales de Reims on Sustainability Studies and the Summer School that is part of it next June.

We'll specially consider how local communities can succeed in combining distributive justice, restorative justice, and interpersonal justice in developing urban agriculture.

François Mancebo, PhD, Director of the IRCS and IATEUR, is professor of urban planning and sustainability at Rheims university. He lives in Paris.

References

Mancebo F., 2015, "Combining Sustainability and Social Justice in the Paris Metropolitan Region", Sustainability in the Global City: Myth and Practice, Gary McDonogh G., Cindy Isenhour C., Checker M. eds, Series New Directions in Sustainability, Cambridge University Press.