What Frank Lloyd Wright Houses Teach about Views, Siting, and Designing from the Inside Out

"Frank Lloyd Wright went to great lengths to make sure his houses never faced north," said Robert McCarter, a Ruth and Norman Moore Professor of Architecture at Washington University in St. Louis, on Friday at his lecture for the Gordon House Conservancy called The Evolution of the American House. McCarter also said that Wright liked to use drapes in homes not only to cut the draft but to create visual privacy while at the same time maintaining auditory connectedness. The architect was particularly sensitive to how occupants of his buildings experienced sound.

The Gordon House

This weekend's lecture was part of a 50 year celebration by the Gordon House Conservancy of Wright in Oregon. The Gordon House is the only house in Oregon designed by Wright and the only Wright building in the Pacific Northwest that is open to the public. It was built in 1964 for Evelyn and Conrad Gordon in Wilsonville, OR. The house is a great example of Wright's "Usonian" houses, which was the architect's acronym for "United States of North America" and an attempt to create a widely affordable and American style of architecture. Conceived during the depths of the Depression, Usonian houses were designed to keep costs low and therefore didn't come with attics or basements and combined the living and dining areas into one large open living space. They were often made of brick or wood or other natural materials. The Usonian Automatic, a 1950s modern rendition, was what Wright coined Usonian homes made of concrete block. The Gordon House was saved from demolition in 2001 and was disassembled and moved to Silverton, Oregon next to The Oregon Garden for public enjoyment.

At the lecture, McCarter covered some important overarching themes behind Wright's residential design that we could all learn from today. Below is a short summary of some of the more salient points from the lecture.

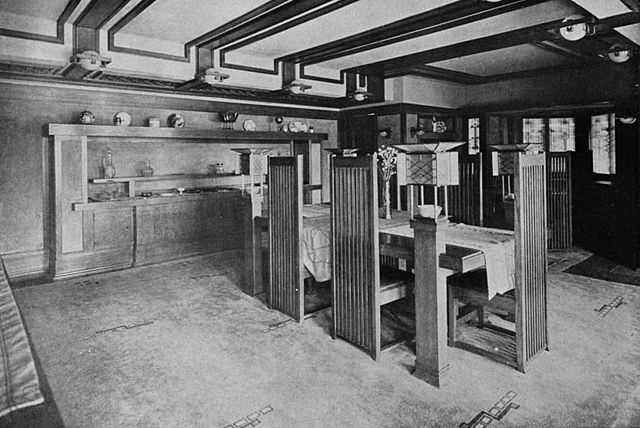

Houses were conceived from the interior, not the exterior

Robie House (Photo by Photocopy of Plate #115, Frank Lloyd Wright, Ausgefuherte Baute, Berlin: Ernst Wasmuth A-G, 1911 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Wright rarely designed a house from the outside in, meaning, he designed the interior first, including the look, feel, scale, and flow of what it would be like to live inside the house. He let the way it looks outside just be a result of the interior layout, instead of the other way around.

Prospect and Refuge

Weltzheimer Johnson House (Photo By Matthew.kowal (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Wright homes are a great architectural example of the concept advanced by early 20th century British geographer Jay Appleton called "prospect (opportunity) and refuge (safety)". Architecturally speaking, prospect entails an occupant's ability to see other people and in general, see what's on the horizon. Refuge, in architecture, refers to the idea of privacy. Wright homes often achieved the perfect balance of prospect and refuge in the most unlikely ways. Even though Wright was all about connecting with nature and having views out to nature, he was also aware of a resident's need for privacy. So he would often design all the glazing at standing height, which offered the occupant abundant views out. But the moment the occupant sat down, either on a dining room chair or a living room sofa, the glazing stopped above seated eye level, so the occupant could enjoy both natural daylight and privacy.

Rhythm in materials

Pope-Leighy House (Photo by Cliff from Arlington, Virginia, USA [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Wright liked to work with rhythm in materials. He liked using materials that naturally provided a rhythm, such a brick or wood. He would use the rhythm of a unit of brick or a unit of wood and create a grid that he would then juxtapose over the whole house, both in plan and in section and elevation. In the Hollyhock House, which was made out of concrete, he was distraught that he could not articulate the rhythm of the interior reinforcing bars and that on the whole, concrete was such a monolithic material without a natural, embodied rhythm that could inform the house's design. Later, when concrete block was invented, refined and made readily available, Wright used this material and reveled in it's 4 inch by 8 inch by 16 inch unit size. The rhythmic repetition of masonry or wood allowed Wright to impose a grid over the house and allowed him to bring order to the chaos of the site he was working on.

Siting

Fallingwater (Photo by Daderot (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Wright was an expert at siting his houses to choreograph the approach, carve out beautiful open space around them and also to create "order out of the disorder of the suburbs." He would sometimes site a house all the way in the back corner to interrupt the conventional rhythm of suburban lots. He would also site his homes in deference to nature. For example, if there was a great big tree in the middle of a lot, he wouldn't tear down the tree out of expedience, but rather design around it. The most famous example of Wright's bold siting is Fallingwater residence in Bear Run, Pennsylvania. There he sited the home over a waterfall, so that the building became a living part of it, instead of merely siting it to have a view of the waterfall.

The Shape of the House

David Wright House (Photo by Lockley (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Wright houses range in shape from a rectangular box to a series of triangles to a spiral circular shape. But these shapes were never arrived at arbitrarily. The shapes of Wright houses are directly a result of interior choreography of what a resident could see or hear and/or of a response to the site. For example, the Ebsworth Park House in Kirkwood, Missouri, is designed on a hexagonal grid, resulting in a series of connected 120 degree triangles in plan. The 120 degree angle provided a wide an embracing interior space, which is great for large living and dining spaces. And the David Wright House in Phoenix, Arizona, is a spiral in plan from which you ascend to the living quarters from an exterior ramp that wraps the interior core of the house. The spiraling ramp slowly reveals a closer and closer view of the adjacent Camelback Mountain as you go up. And the spiral also allows for an interesting and well-executed balance of prospect (views out) and refuge (privacy) on the interior as well.

McCarter, a Wright scholar and connoisseur, has the honor of currently living in a Wright house in St. Louis. And he confided that "when you sleep in a Wright house and wake up in it the next day, it changes your life."

Lead photo credit: Robie House. Photo by Lykantrop (Own work) [see page for license], via Wikimedia Commons