Citizen Science in the City: Lessons from Melbourne's BioBlitz

By Chris Ives, Yvonne Lynch, Caragh Threlfall, and Mark Norman

Every day, citizen scientists contribute their time and energy to support thousands of research projects around the world (Bonney et al., 2014). They collect, categorize, and analyze data, generously volunteering their time and their personal resources in return for little other than recreational enjoyment or the personal satisfaction of helping others.

An example of Melbourne's biodiversity: the crested pigeon. Photo: Museum Victoria

However, as we learnt from Melbourne's recent BioBlitz (a public event to generate a snapshot of the city's biodiversity), the benefits citizen scientists receive from experiencing biodiversity firsthand and the value of public engagement in managing urban ecosystems can be just as important as the data that is collected.

Citizen science in history

In the early 2000s, scientists at the University of Washington, Seattle, outsourced critical scientific work on protein structure prediction to citizen scientists. Within three weeks, those citizens produced a near-exact model for a protein whose structure had eluded scientists for more than a decade. In fact, as far back as the 17th century, naturalists such as John Ray (1627-1705) were commandeering the goodwill of friends and family to assist in recording plant and animal classifications. Ray's work paved the way for Carl Linnaeus, the "father of modern taxonomy," and thousands of others.

There are many such examples of positive and unexpected contributions of citizen science to knowledge, and interest in citizen science for urban nature is growing, as evidenced by recent essays on TNOC. Yet, in the peer reviewed literature, the validity of citizen science outputs remains in doubt.

For those city practitioners and scientists who wish to advance knowledge of urban nature, there are some serious questions that need to be asked. As technological sophistication increases and barriers to rapid data collection and analysis subsequently decrease, are we denying an untapped army of citizen enthusiasts the opportunity to collaborate to benefit urban nature? Through evaluating our experience with the Melbourne BioBlitz, we argue that the potential for citizen scientists to contribute significantly to the stewardship of urban biodiversity is very great indeed.

The Melbourne BioBlitz

Another example of Melbourne's biodiversity: White's Skink. Photo: Museum Victoria

Last year, the City of Melbourne called on citizen scientists to help develop the city's first Urban Ecology and Biodiversity strategy by participating in a BioBlitz—an intense period of dedicated mass biological surveying.

Melbourne is a biodiverse city, blessed with parks, rivers and a bay all on its doorstep (Ives et al., 2013). However, Melbourne's biodiversity is challenged by a combination of factors including climate change, rapid population growth, and land use change. In addition, an increasingly urbanised public has less and less familiarity with nature and wildlife.

The City of Melbourne plans to address this issue through the development of a contemporary strategy that aims to bring biodiversity to the fore of urban design and planning in the city. However, apart from a public tree database and limited biodiversity data for three parks, city officers had no comprehensive records of biodiversity. Without such data, it is difficult to set meaningful targets and goals for the strategy. Wide-scale biodiversity data collection by professionals in a short time frame would have been resource intensive and cost prohibitive. The concept of a BioBlitz represented an appealing method of data collection for a number of reasons—such an initiative would involve the community in the development of the new biodiversity strategy from the outset, would increase biodiversity awareness and education levels, and could remove private realm access barriers.

The Melbourne BioBlitz was conducted over 15 days from 31 October to 14 November 2014. During that time, more than 700 citizens participated in the initiative, collecting over 3,000 biodiversity records for the city. Of those 3,000 records, 600 sightings were identified to species or genus level and 500 different species were identified by common names. Groups of taxa identified included insects, mammals, reptiles, birds, plants, fungi and aquatic life. Invertebrates and birds together accounted for 90 percent of all sightings across the municipality.

Rare moths that had not been sighted for decades were discovered fluttering around Fitzroy Gardens, the city's most central and most visited park. Hidden amongst the canopy in the same park, participants found microbats that have not been encountered in the same abundance in any other urban park in the area. Melbourne's media became particularly enamoured with the local biodiversity, with conversations and observations on butterflies, bats, bees and birds making positive national headlines.

The BioBlitz employed a variety of methods to facilitate citizen participation, from expert led surveys and activities to a variety of online tools including Bowerbird (an interactive biodiversity data repository), Instagram, Twitter, and the City's own Participate Melbourne website. The preferred method for data capture during the BioBlitz turned out to be handwritten sightings, with over 750 sightings submitted in this format. Submissions to Participate Melbourne and Bowerbird closely followed the tally from handwritten sightings, with 744 and 739 uploads, respectively. Participants used Instagram and Twitter to a much lesser extent; participants used Twitter primarily to promote the BioBlitz rather than to record sightings.

This unique event represented Melbourne's first foray into citizen science to inform policy development. The lessons learned offer an ideal basis for reflection on whether citizen science can be an effective means for influencing urban policymaking.

Lessons learned

Our experience with the City of Melbourne BioBlitz has provided many insights, both about how to administer a citizen science project as well as how the general public responds to urban nature. Typically, the primary object of citizen science programs is to generate data that can be used to answer scientific questions. The efficacy of the BioBlitz for this function has yet to be demonstrated. Despite the huge number of species observation records, the design of the event has made it impossible to determine what proportion of the biodiversity of Melbourne was represented in the survey. The BioBlitz does, however, provide a baseline dataset that can be expanded. Of greater value than the data that citizen scientists collected was the level of public engagement that occurred. We found that BioBlitz participants expressed a high degree of interest in contributing to the development of the City's urban ecology and biodiversity strategy. This is clearly a novel approach to public engagement with policy and it has potential to be adopted in other jurisdictions around the world.

Regardless of the robustness of the scientific data gathered, the event helped to make visible the often-invisible ecology of the city. This was true for both scientists and the public. Scientists made many comments about their surprise in finding so many species (particularly of invertebrates) in the middle of a major capital city. Perhaps even more rewarding was the surprise and joy expressed by the community participants at the animals they found in the city. Indeed, many did not realise before the event that microbats live in Melbourne! The event made evident that people have a natural curiosity for nature, which was surprisingly easily accessed. Further, the educational value of the event for children was evident from their many questions and fascinated expressions as they were shown around the gardens and green spaces.

Local residents participating in the BioBlitz. Photo: City of Melbourne

The BioBlitz helped to foster a sense of stewardship towards biodiversity in local residents. While this is difficult to demonstrate empirically, anecdotal evidence suggests that many participants will undertake new gardening practices that enhance biodiversity in their own backyards. We felt that the experience of biodiversity through the BioBlitz had a far greater impact on people's behaviour than the presentation of information ever could.

Conversations with participants also pointed to the benefit of the BioBlitz as an exercise in building social cohesion and connection with local government. Participants made positive comments about the non-commercial nature of the event and were pleased that it was free to attend. Clearly, there is a strong community desire for these types of programs, with benefits extending far beyond purely ecological outcomes. The positive sentiment towards the event was even expressed strongly in numerous tweets and Facebook posts. For example:

"I'm not generally keen on spiders, but they all have their role to play."

"Surprisingly, since I took part in #bioblitzmelb I have a newfound respect for flies."

"I'm loving all of these native bees! Who'd have thought that we had so many!"

Finally, one of the biggest lessons that we learned from the experience is the value of collaboration between different organisations and individuals within the city. The BioBlitz was supported by a range of partners (Museum Victoria, RMIT University, University of Melbourne, the Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology, naturalist groups, 'friends of' groups, non-government organisations, and many natural resource management agencies). The event represented a unique opportunity for collaboration between multiple researchers and scientists from these institutions that would not otherwise have occurred. Although each organisation had its individual agenda in participating in the BioBlitz, they all shared an important vision: helping to enhance Melbourne's natural environment and biodiversity. Museum Victoria, for example, has both an interest and a mandate to document and promote the natural places and animals of Victoria. University academics eager to make a tangible difference to the future of the city were also given opportunities to pursue research questions related to the event. The BioBlitz therefore provided the ideal vehicle for organisations to work together to achieve shared and individual goals. Encouragingly, the connections forged through such an event persist long after its conclusion and have potential to enhance biodiversity initiatives in the city in the future.

Practical guidelines for implementing an urban BioBlitz

There are many insights that we gained for running a successful BioBlitz that we hope can assist anyone planning an event in the future, regardless of your location or budget!

- Foster collaborations with local organisations

The success of our event was largely a reflection of strong partnerships between the City of Melbourne and our diverse range of partner organisations. The partnerships brought together people with complementary skills and allowed the event to reach a much wider audience than would have otherwise been possible.

- Draw on the experience and talent within your organisation

Organisations such as local governments, Museums, and Universities have a range ofpersonnel that can assist with executing a successful event. The Melbourne BioBlitz not only drew on the scientific expertise within participating organisations, but also on the expertise of staff in communications, media, events management, horticulture, park management and cultural heritage. We also ran staff-specific events and staff photo competitions to increase the participation of staff within each organisation and to get them engaged with issues of urban biodiversity.

- Establish an interactive website

As part of the Melbourne BioBlitz, we established a website dedicated to the event. The website detailed the aims of the event and the pathways for participation, from joining an expert-led tour to downloading a toolkit that provided step-by-step instructions for seeking biodiversity in one's own backyard. Apart from being a repository of information on the event, the website allowed people to upload their own photos of biodiversity from around the city. This allowed members of the public to contribute meaningful data on Melbourne's urban biodiversity, which is subsequently being used to plan how to better manage biodiversity with the city.

- Develop a toolkit to assist people to participate when & where it suits them

To ensure people could participate in the BioBlitz at any time, we developed a toolkit that could be downloaded as a PDF on our website. The toolkit provided hints and tips for finding biodiversity, such as where to look for reptiles or insects, and what times of day are best for finding birds and mammals. It also detailed the various pathways available for people to submit their observations, from mailing or emailing a form to uploading photos to our website. The toolkit allowed people to engage with the BioBlitz as citizen scientists in areas that our facilitated events couldn't reach, such as their backyards, streetscapes, local parks, and even businesses. As a result, the spatial reach of the event was far greater than we could have ever achieved with the finite number of events we could host ourselves.

- Utilise web-based biodiversity databases and phone apps

There are many web-based databases currently in use to collate biodiversity data from around the globe, such as iNaturalist. Fortunately, some of these databases have associated platforms for uploading data via phone apps or online forms. In Australia, the Federal government has created the online Atlas of Living Australia (ALA), which hosts all of Australia's biodiversity data. To facilitate the upload of data captured during events such as BioBlitzes, Museum Victoria has created an interactive website called Bowerbird, which can be used by citizen scientists to create biodiversity records for Australia. All data uploaded to Bowerbird is linked to Australia's national database (ALA), allowing citizens to contribute to the collection of meaningful data, which is being used across the country by scientists and policy makers. Wherever possible during Melbourne's BioBlitz, we encouraged staff, participants, and expert leaders to take photos of the biodiversity they were finding across the city and to upload their photos to Bowerbird. Not only does Bowerbird allow for the identification of species within each photo, it also links directly to the ALA, allowing for the development of a spatially explicit biodiversity data layer that can be used to help develop biodiversity policy for the city. The use of Bowerbird during Melbourne's BioBlitz provided a complementary method for data collection in addition to our website and toolkit.

- Use conventional and social media to your advantage

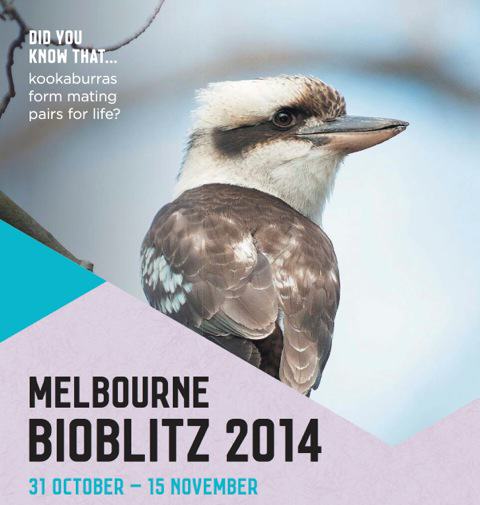

One of the 'did you know' posts used to generate public interest in the BioBlitz.

The Melbourne BioBlitz attracted its fair share of radio interviews and newspaper articles, but we also developed a social media campaign that we designed to sustain interest in the event at key times throughout its duration. Not only did we have all institutions involved in tweeting before and during the event, we also created a hashtag that was used on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, #BioBlitzMelb. We used a series of sponsored posts on Facebook to advertise the event, which assisted enormously with increasing its reach. To generate interest, each post included a new photo of an animal or plant that was known to occur in the city, and a fun fact about each species. This series of 'Did you know……' posts received between 700 and 45,000 views, and turned out to be the most successful way of increasing participation in the event.

- Consider hosting events across a range of locations and times

We hosted 52 events over a two-week window, instead of running a more traditional, intensive 24-hour BioBlitz event. The event schedule was designed to span times critical to fauna and included sites for which biodiversity data was needed. We also designed the schedule to include weekday and weekend events that captured a wide range of participants. We included early morning dawn bird surveys, lunch-time invertebrate walks, and nocturnal bat and moth surveying events that attracted people before work, workers on their lunch breaks, tourists, families, school groups, and local residents. We also chose a mix of locations in the city to hold these facilitated events: some that we knew would be great places to spot birds, others for which we had no data at all. Our chosen locations had a range of facilities such as a power sources, shelter, toilets, parking, and public transport to ensure everyone could get to each location. Through this mix of sites and times we were able not only to acquire information on a wide range of taxa, we were also able to highlight the fantastic array of wildlife that calls Melbourne home in unexpected places, helping to create a sense of excitement about the potential for Melbourne to be a biodiverse city.

Chris Ives, Yvonne Lynch, Caragh Threlfall, and Mark Norman

Melbourne