How sprawl worsens the impacts of drought and how smart growth can help

If you live in the US and have been outside lately, chances are you don't need to be reminded that this is the hottest summer many of us can remember, and also one of the driest, following a relatively dry winter and spring. Heck, you don't even need to go outside to know these things if, like me, you were one of the millions of Americans whose homes or workplaces experienced prolonged power outages a couple of weeks ago.

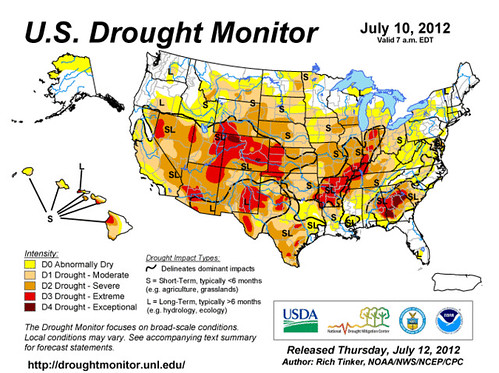

But allow me to remind you anyway, or perhaps just commiserate with you, for a moment: As Michael Pearson and Melissa Abbey wrote earlier this week for CNN, our country is experiencing its worst drought in over half a century. At least 55 percent of the US was in moderate-to-severe drought as of last month, and things have only gotten worse since. Indeed, June 2012 ranks as the third-driest month nationally in 118 years, write Pearson and Abbey. Among consequences, 38 percent of the corn planted in the 18 leading corn-producing states is considered to be in poor or very poor condition this week, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Now, I'm not naïve enough to claim that the way we have built suburbs and cities over the last several decades is a proximate cause of drought, but sprawling land use can exacerbate some of its impacts, in at least two ways. First, the large-lot residential development characteristic of sprawl uses significantly more water than do neighborhoods built to a more walkable scale, contributing to water shortages. According to EPA research, for example, in Utah 60 percent of residential water use is for watering lawns and landscaping; households on 0.2-acre lots use only half as much water as those on 0.5-acre lots. In Seattle during peak season, households on 0.15-acre lots use 60 percent less water than those on 0.37-acre lots.

The Smart Water Report by Western Resource Advocates provides additional evidence:

"A case study from Las Vegas reveals that a decrease in housing lot size over the past two decades resulted in a slow but steady drop in average per account water use. Another case study from Tucson shows that astounding water savings can be realized if new urban and suburban developments incorporate mixed uses, higher densities, water reuse, and water-efficient Xeriscape landscape design and irrigation practices. In sum, water use resulting from urban sprawl can be reduced by modifications to development densities (e.g., lot sizes), the chosen type of developed landscape, and the source of landscape irrigation water.

"These findings provide encouraging news for urban planners and water managers: water use efficiency improves through 'smart development.' Municipal zoning ordinances, land development standards, comprehensive plans, and inter-municipal regional plans all play key roles in creating sustainable development and, as a result, more sustainable water use."

The second way in which suburban sprawl exacerbates the impacts of drought is by spreading more pavement around watersheds, sending billions of gallons of rainwater into streams and rivers as polluted runoff, rather than into the soil to replenish groundwater. Again, EPA research is instructive: more compact growth patterns with an average of eight houses per acre

By the way, I should note that increasing average residential density to, say, eight homes per acre (or whatever the community goal) to achieve watershed benefits does not mean that no lots would be larger than an eighth-acre. What would be required is building to an average of eight homes per acre, which could be achieved through various combinations of multi-family complexes, townhouses, small-lot homes and large-lot homes. I'm also not judging people who water their lawns and/or gardens; I water my own, although I'm fortunate for this purpose to have a small lot. But the more efficient our land use, the more irrigation is possible without damage to water supply, at least in the Northeast where I live. In arid parts of the country, it becomes harder to reconcile household irrigation with sustainability.

A decade ago, my NRDC colleague Deron Lovaas co-authored a report on the subject of runoff and groundwater supplies. A summary released by NRDC with our research partners American Rivers and Smart Growth America points to enormous amounts of water waste from sprawl:

"In Atlanta, the nation's most rapidly sprawling metropolitan area, recent sprawl development sends an additional 57 billion to 133 billion gallons of polluted runoff into streams and rivers each year. This water would have otherwise filtered through the soil to recharge aquifers and provide underground flows to rivers, streams and lakes."

While sprawl may not cause drought, nor smart growth solve it, both need to be considered in the discussion of how to move toward a more resilient future. (On an interesting related point, Don Carter of Carnegie Mellon University makes a compelling case that over the long run America's older, post-industrial cities may be able to absorb growth more sustainably than cities in the Sun Belt because of their greater water resources.)

I'll conclude with a couple of personal anecdotes, starting with one that I also shared three years ago (in a post now so old it doesn't even show in my blog's archives anymore). From time to time, my wife and I travel to a wonderful, old-fashioned Blue Ridge Mountain retreat in southwestern Virginia called Peaks of Otter. It's on the Blue Ridge Parkway and on the way from our home in DC to my mother's residence in North Carolina, making for a convenient stopover. One of the highlights at Peaks of Otter is Abbott Lake, which has an island in the middle, right in the vista from the dining room looking toward Sharp Top mountain.

Except, on a visit during another drought, the island wasn't there. We couldn't quite figure out why the scene looked a little unfamiliar, like something was off. Eventually we compared what we were seeing to the standard photos of the lake and mountain: the lake waters had receded to the point where what used to be the island had become part of the shore. What used to be the lake had become a wetland. It was shocking.

Now, alteration of a bucolic scene is a relatively benign consequence of drought, and not even that unpleasant for the human visitor, apart from being a bit unsettling. But many consequences of drought are not so benign. On a trip to a different part of the Blue Ridge earlier this month, the view from our hotel was dominated by forest fires in Shenandoah National Park. I know that states in the western US must cope with forest fires almost routinely, the ones near Colorado Springs recently quite serious, but they are rare in this part of the country.

Would sprawl in the DC, Atlanta, or even Denver suburbs have an impact on a lake in the Blue Ridge or fires in Colorado or Virginia? Highly unlikely. But these dramatic scenes remind us of the severity of drought in recent years. The impacts affect everything from corn crops to our ability to grow food in our back yards to drinking water supplies. As we look for ways to mitigate and adapt to the water impacts of evolving climate patterns, land use practices belong in the conversation.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

Kaid Benfield writes about community, development, and the environment on Switchboard and in the national media. For more posts, see his blog's home page. Please also visit NRDC's sustainable communities video channels.