Is running freeways through cities a costly mistake?

I am of the opinion, which is by no means universally held, that the Interstate Highway System, whose construction was begun in the 1950s, was good for America, or at least a net plus when it comes to travel between cities. As I have written before, I am old enough to remember when the early parts of I-40 were built in western North Carolina, allowing my family to reduce a two-hours-plus trip to visit my grandmother down to 90 minutes. This meant we could visit her on a weeknight after my parents got off work. I'm sure that the system also generated all sorts of economic benefits.

Freeways as traffic movers

But that's regarding travel between cities and metro areas. Within metro areas has been another matter altogether. There the story has been mixed at best, and I would argue that within large cities, freeways – which have never really been free, by the way – have proven to be a perhaps well-intended but often decidedly bad idea. For the most part, they do a terrible job of conveying traffic within densely populated areas. As many a harried soccer mom, delivery driver, commuter or contractor can attest, getting to one's destination within a reasonable amount of time has become largely a matter of luck.

To offer a case in point, here's another story about visiting relatives. My parents-in-law live in the suburb of Fairfax, Virginia, about 20 miles from our house in DC. My wife's mom recently had major surgery, so my wife has been spending more time than usual at their house, frequently staying overnight. I drove out to join them two weeks ago on a Saturday night.

So, freeways don't work that well even in the suburbs. Where they have been built In the hearts of big cities, they have frequently become roads to avoid, unless you happen to be driving at a very off-peak hour, like when most people are asleep. So they don't convey traffic very well in cities, either.

Freeways and neighborhoods

But that's not the worst part, actually. Inside cities, where freeways were built through once-intact neighborhoods, they have done damage to our social fabric that has proven impossible to rectify, most frequently in low-income and minority neighborhoods. Many of those neighborhoods were struggling even before the freeways drove concrete stakes through their hearts.

In my post on this subject about a year ago, I quoted my friend and former co-author Don Chen on the subject. Some of the passage that I quoted from our 1999 book, Once There Were Greenfields, bears repeating here:

"During the first decade of Interstate highway construction, 335,000 homes were razed, forcing families to look elsewhere for housing . . .

"In many cases, the 'urban blight' targeted by the new road construction simply meant African-American communities—often thriving ones. A great body of work shows that urban freeways destroyed the hearts of African-American communities in the South Bronx, Nashville, Austin, Los Angeles, Durham, and nearly every medium to large American city . . .

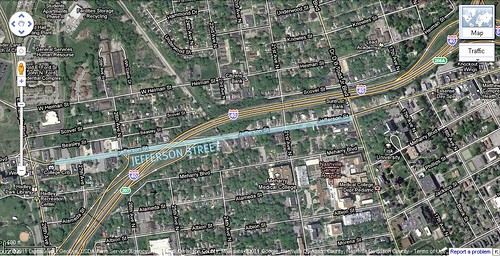

"In Tennessee, plans for the construction of Interstate 40 were in fact redrawn to route the highway through the flourishing Jefferson Street corridor, home to roughly 80 percent of Nashville's African-American-owned businesses. Not only did the construction of I-40 destroy this commercial district; it also demolished 650 homes and 27 apartment buildings while erecting physical barriers separating the city's largest African-American universities: Fisk University, Tennessee A & I University, and Meharry Medical College."

In another post, I recounted the bleak story of how the Claiborne Expressway in New Orleans bifurcated that city's culturally rich Tremé district. Among the casualties were a popular Mardi Gras parade route lined with majestic oak trees and a thriving corridor of African-American businesses some called "the black people's Canal Street" (great, extended quotation in my earlier post).

Versions of this story can be told all across the country. But the damage doesn't stop there. Trampling on neighborhood fabric, it turns out, was a sort of social insult added to very real economic injury. Writing on his blog Original Green, my friend Steve Mouzon examined property values along an eleven-block stretch of a street that runs perpendicular to and underneath I-65/70 in Indianapolis.

Steve reasonably suggests that, although the neighborhood on the east side does not match that on the far west for per-acre value, the increments of change as one moves from west to east likely would have been more gradual, rather than dramatic, without the freeway. While Steve's analysis is based at best on a small sample size and an informal calculation by a non-economist, it sure seems intuitive and directionally correct to me. My guess is that freeways have probably created value in the suburbs but frequently diminished value in city centers. I'm sure there are more sophisticated studies on the subject, but I haven't had time to research them.

Moreover, on the Texas blog Walkable DFW, Patrick Kennedy ("larchlion") has constructed a fascinating series of maps correlating the geography of roads designed for high speeds in Dallas (and, in a couple of cases, Philadelphia) with a number of other variables, including crime, Walk Score walkability distribution, outdoor café seating, traffic fatalities, and vacant land. Basically, freeway corridors are associated with higher crime, reduced walkability, the absence of outdoor seating, high traffic fatalities, and increased vacant property acreage.

Never meant to be

There may be cases where urban freeways have been a net plus for residents of the cities where they were built (apart from what they may have meant for non-residents passing through), but my guess is that they are few and far between.

In particular, President Dwight D Eisenhower is generally credited with bringing the Interstate Highway System to America. As a brilliant wartime general, he had seen the necessity of being able to move troops and equipment quickly from one location to another, and he had seen the first German autobahns. While others had entertained the idea of freeway construction, and prototypes like the Pennsylvania Turnpike had already been built, it was Eisenhower who pushed the idea as a national system and priority and made it happen. The system now bears his name.

But Eisenhower never intended that the Interstates be built through densely populated cities. A memorandum of a 1960 meeting in the Oval Office, available in the archives of Eisenhower's presidency, makes this crystal-clear:

"[The President] went on to say that the matter of running Interstate routes through the congested parts of the cities was entirely against his original concept and wishes; that he never anticipated that the program would turn out this way . . . and that he was certainly not aware of any concept of using the program to build up an extensive intra-city route network as part of the program he sponsored. He added that those who had not advised him that such was being done, and those who steered the program in such a direction, had not followed his wishes."

The Secretary of Commerce and head of the Federal Highway Administration were in the room. (Thanks to urban transportation whiz Rick Hall for finding this memo.)

Other approaches

Some cities have elected not to rebuild freeways when they reach the age where costly repairs are required but, instead, to replace them with surface boulevards. The best known of these is in San Francisco, where a 1989 earthquake famously knocked out the Embarcadero Freeway. It has now been replaced with "a tree-lined boulevard that blends alternative modes of transportation, including a perfect pedestrian promenade, a bicycle corridor and a popular streetcar line."

Then

Now

The change has increased property values, attracted investment, and restored scenic views previously blocked by freeway infrastructure, all without harmful effects on traffic. Back in Dallas, Kennedy "conservatively" estimates that replacing a segment of I-345 in the city with a surface-level boulevard could attract $750 million worth of new investment and increase tax revenues from adjacent properties six-fold.

Other cities have "capped" freeways with parks in an attempt to restore or create urban fabric above the roads without tearing them down. Boston's famous "Big Dig" that buried that city's Central Artery is one example. Seattle also has a park above a freeway, and there are a number of proposals currently working their way through various bureaucracies, including a breathtaking concept for Hamburg, last year's European "Green Capital."

For readers who may be interested, there are a number of resources on the subject of freeway removal. For example, the Institute for Transportation & Development Policy just released the first part of its new report, The Life and Death of Urban Highways. In addition to the Embarcadero, the full report (due this month) promises case studies of other freeway teardowns or decisions not to build in five other cities, including Portland, Milwaukee, Seoul, and Bogotá. The city of Seattle has also compiled a set of case studies on freeway removal, available as a PDF here. The Congress for the New Urbanism maintains a list of twelve proposed "freeways without futures" (including the Claiborne) that it believes should be torn down.

Go here for a very well-produced short video of CNU president John Norquist explaining why cities on the list would be better off without the aging roadways.

Kaid Benfield writes (almost) daily about community, development, and the environment. For more posts, see his blog's home page. Please also visit NRDC's Sustainable Communities Video Channel.