Boston's Emerald Necklace Sets the Standard for Linked City Parks

I'm fortunate to be participating in this week's annual meeting of one of my favorite organizations, the American Society of Landscape Architects. Since the conference is being held in Boston, this gives me a great opportunity to highlight ASLA's superb Landscape Architect's Guide to Boston, published online and similar in concept and format to the organization's guide to Washington, which I highlighted here.

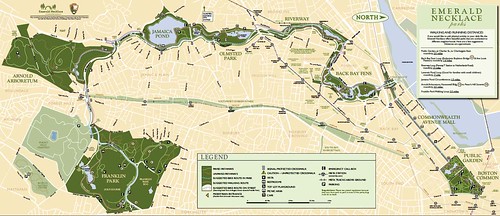

The guide begins, as it must, with Boston's "Emerald Necklace," described as a 1,100-acre chain of green spaces connecting the Boston Common—in the heart of the city and dating from the colonial period—and the adjacent 1837 Boston Public Garden to five additional parks and an arboretum designed by legendary landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted: The Arnold Arboretum, Back Bay Fens, Franklin Park, The Riverway, Olmsted Park, and Jamaica Pond.

All are linked by parkways and waterways; all the Olmsted projects were developed in the late 1880s. The guide doesn't specifically include the mile-and-a-quarter Commonwealth Avenue Mall – which links the Public Garden and the Back Bay Fens – as a distinct part of the chain, but the city of Boston's description does.

From Boston Common to Franklin Park (home of Boston's zoo), it is approximately 7 miles by foot or bike. The Emerald Necklace is the only remaining extant linear park designed by Frederick Law Olmsted.

I have visited some of those, and the new guide makes me want to get on a bike and visit all of them. According to the Necklace's Wikipedia entry, the system comprises half of the City of Boston's park acreage, along with parkland in the Town of Brookline, and parkways and park edges under state jurisdiction. More than 300,000 people live within its watershed area, and the parks draw over a million visitors per year.

Though the chain of parks looks as if its components are as nature constructed them, they in fact are designed landscapes. From the city's description:

"Study these green spaces more closely and you'll find they are far from naturally occurring phenomena. They are feats of engineering, marvels of visionary urban planning, corridors of transportation, contributors to the public health, and a canvas upon which an artist has worked in plants, trees, earth and water instead of oils.

"The artist we refer to here is Frederick Law Olmsted who, for his vision and craft, is known as the father of landscape architecture . . . Olmsted designed this park system in the later 19th century to provide a common ground to which all people could come for healthful relief from the pollution, noise and overcrowding of city life. Carriages, horseback riders and pedestrians could enjoy their recreations, and Bostonians could find places for both active play and quiet contemplation. He reshaped the topography to solve major drainage and sewage problems and to create a rustic environment."

I believe that cities need nature to soften the sometimes harsh or overwhelming effects of pavement and density. We need that density – if maybe not quite so much pavement – in order to create healthy, walkable urban environments and to limit encroachment on rural land outside cities. But nature can make it so much more livable and appealing. I sometimes write about what I call the paradox of smart growth – urban density reduces environmental impacts across a region, but can increase them locally, at the neighborhood scale. Parks and other forms of nature provide an antidote.

The Landscape Architect's Guide to Boston isn't limited to the Emerald Necklace, or even to parks, though it covers those subjects extremely well. Take a look to find everything from community gardens to green public alleys to outdoor art installations. But the Necklace, which gets so many things right, is a great place to start.

Related posts:

- Best & worst cities for convenient public parks, and why it matters (June 19, 2013)

- Measuring life quality: the Boston Indicators Project (May 13, 2013)

- World's second-largest rooftop farm takes root in Boston (March 7, 2013)

- New online guide highlights the (sometimes hidden) beauty of Washington, DC (September 24, 2012)

- Nashville's new hypergreen riverfront park (April 27, 2012)

- A remarkable grassroots revitalization matures and thrives in Boston (March 26, 2012)

- The good news: we're getting more city parks. The bad news: we have less money to take care of them. (December 13, 2011)

- How pocket parks may make cities safer, more healthy (November 23, 2011)

- How parks can help revitalize distressed neighborhoods (March 16, 2011)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

Kaid Benfield writes about community, development, and the environment on Switchboard and in the national media. For more posts, see his blog's home page. Kaid's forthcoming book, People Habitat: 25 Ways to Think About Greener, Healthier Cities, will be released in January.