History of Street Trees in Paris

This week, all three of our posts are devoted to the history of street trees in Paris – a city that, as we conclude in today's piece, could just as easily be called "City of Trees" and "City of Lights." -LM

Paris has been around for a long time, too long to cover in only one post, so this is the first of three that I want to share with you about the amazing history of street trees in Paris.

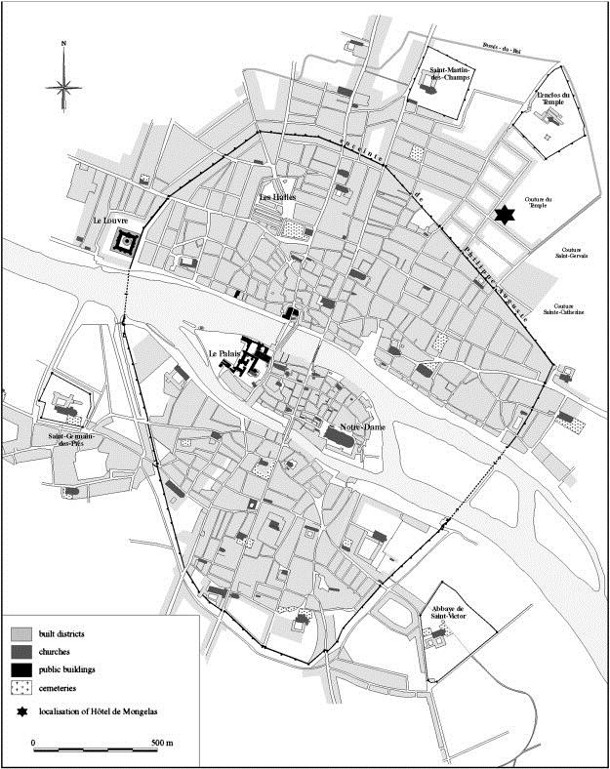

Paris during the Middle Ages was about 1.5 miles (3 km) across and about 1 mile (2 km) long, a far cry from contemporary Paris! A few years ago on this blog, we conducted a survey of world famous urban foresters, landscape architects, and urban planners, to find out, based on their experience, which cities world-wide demonstrated the best street trees? (See previous blog) Paris emerged as the overwhelming winner. I have included two historic maps, one from 1300 and one from 1552, which render it hard to believe that Paris would ever become globally famous for its trees.

Figure 1: This map shows the street grid and blocks within Paris, France, in the beginning of the 14th century (1300-1325 AD). It also indicates the localisation of the archaeological site, Hôtel de Mongelas. Image credit: Science Direct

The original Roman Walls of Paris enclosed 25 acres (10 hectares). Figure 1, above, shows a walled Paris, occupying an area of less than 1 square mile (< 250 ha). By 1300 the Paris Citadel was 625 acres, less than 1 square mile (250 ha). In that area alone, I counted 210 city blocks, at least 74 streets/alleys, and about 12 city gates. Blocks had a great variety of sizes, but averaged about 2 acres, or 200m² x 400m², in size. (For reference, this is comparable to the average block size of many modern United States cities.) However, these historic Parisian blocks had no setbacks, and the sidewalks and streets were combined for a typical street width of between 10 to15 feet (3m – 4m). Housing was compact, vertical, and connected by streets wide enough for a man on a horse and little else.

Outside the northern walls of Paris stands the Priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs. There is one through street north/south, the Old Roman Road, that crosses the Seine. It is now known as the Rue St. Martin (to the north) and Rue Saint Jacques (to the south) and Rue de la Cité somewhere on the island, Ile de la Cité, and continues south past the southern city walls, where Notre Dame Cathedral still sits.

Figure 2, below, shows a more contemporary view of Paris from 1552. Somewhat confusingly, the top of the map from 1552 does not face north; likely this was simply an artistic choice. To compare it to the map shown in Figure 1, simply rotate it 90 degrees clockwise). The north side in Figure 2 shows the earlier (1300) wall and a later wall which greatly expanded the city. It also shows left bank of the Seine with lots of trees on its banks.

Figure 1: 1552 A.D. map of Paris, by Truschet and Hoyau. For comparison with Figure 1, rotate this map 90-degrees to the right (clockwise) so that the larger portion of the walled-city is at the top (north) of the page. Observe that the road that runs north-south through the center of the city Old Roman Road persists on its original alignment after 2000 years. Image credit: Bibliothèque de l'université de Bâle, Kartenslg AA 124.

L. Peter MacDonagh, ASLA, is the Director of Science + Design at The Kestrel Design Group.